When creating multilingual content, there is a fine line between staying true to the original version and adapting it to the target language for a maximum of authenticity. Hence, linguistic challenges have been plentiful during the translation and correction of learning units into German.

Code Switching and Formal Language

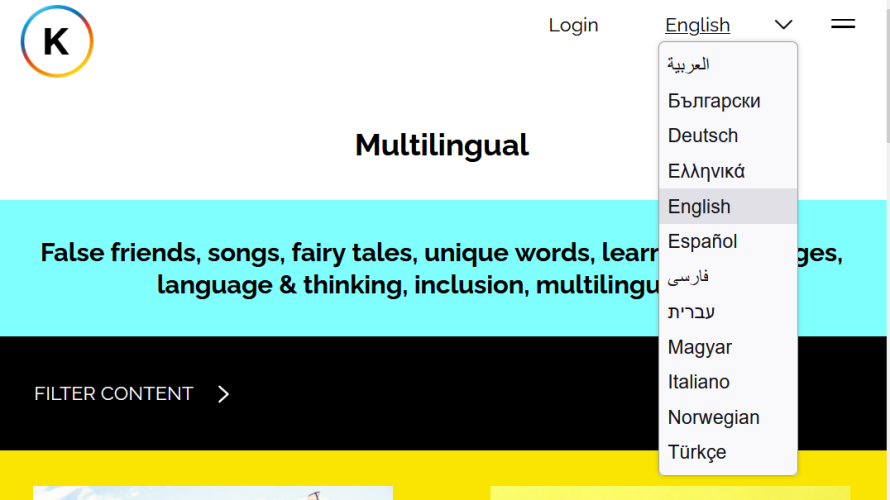

KIDS4ALLL has always been thought of as a multilingual project. The platform targets children, teens and their educators from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. The idea is not to replicate school, but to reinvent it to a certain extent – to make learning fun, by having a colorful website, varied activities, interactivity like quizzes and the cooperative ‘buddy’ system. However, how should this show in our use of language? Does it mean that we should use an informal tone, or is this inappropriate because it is about written language? In our team, we had some discussions, sometimes even about the smallest details of the German language. “Alone” can be translated as allein (more formal) and alleine (informal). “You can already prepare questions” could be put Du kannst das schon einmal vorbereiten or Du kannst das schon mal vorbereiten (more informal).

Interestingly, one learning unit focuses on exactly this topic of adapting one’s language according to the audience: “Get the right code!”. It makes the kids and teenagers aware of the different language codes they use when writing an email to a teacher or a message to a friend via social media.

Gender Inclusivity

Another advantage anglophones have is the relative ease with which they navigate gender-inclusive language. English has always offered the convenient ‘they’ for singular usage that can be used in sentences like ‘The best participant would be told to pick up their award on Saturday’ (avoiding ‘her’ or ‘his award’). In German, the gender agenda is on a different level: Not only is there no alternative to he (er) and she (sie) in the third person singular – almost every noun concerning a person is gendered (think of friend: male Freund, female Freundin). Our team has decided on one of several options for including both forms and avoiding the generic masculine: the colon for Freund:in that appears increasingly often in the German news, in books and on websites. There are also certain avoidance strategies, like saying Lehrende (“the ones teaching”) or avoiding certain nouns and referring to a Freundeskreis (“circle of friends”) instead.

Typing it Right

The deep mystical forest of typing hides one mischievous contemporary: spelling. The commas, question marks and slashes are so deeply ingrained in our daily usage of language that we hardly stumble upon them or stop to question how they essentially guide us through the flow of written text. This means it is sometimes hard to notice when another language uses punctuation differently. For English speakers, an enumeration ended with “etc.” should be preceded by a comma – but not for Germans! Similarly, French requires a space before their question and exclamation marks (Really ?! Yes !). And quotation marks! Oh, what suffering Germans experience when Google Doc automatically writes down English quotation marks on the upper left and right side: “Oh no”. No, Germans need one on the lower left and the upper right, like this: „Yes, this looks German enough.“

Conclusion

If one thing is evident in the KIDS4ALLL project, it is that translating does not mean simply transferring one expression into another word by word or throwing a paragraph into an online translator – it is about discussing fine nuances, taking distance to a text and reevaluating if it sounds authentic to a native speaker; it is about not getting confused by the spelling of different languages and making peace with the challenges and complications that some languages have and others do not.